Translated by Georgina Fooks

I don’t know if inspiration exists, but I get mine from Agnès Varda. That’s what I told the student who asked me that tricky question a few years back. There are people who find theirs gazing at leaves on a tree on a cloudy day, listening to classical music in the midnight hours, reading Rimbaud at a beach house. My story was simpler: when I was a twenty-something studying film, I watched the documentary The Gleaners and I (2000), and so I wanted to be a filmmaker. I was struck by the way she put people who rummage through others’ waste on the big screen. But making films became impossible for me. Chance was not on my side nor were the means to do so, and so I turned to literature. Later, I saw the documentary Daguerréotypes (1975) and immediately wanted to write about Barrio Brasil in Santiago de Chile, just as she portrayed the traders in their shops and her neighbours on the Rue Daguerre in Paris.

Agnès Varda passed away on the 29th of March, 2019, at the age of 90. Although I never met her, every now and then I feel a certain nostalgia about her absence. It’s a different sort of nostalgia, less sad than other kinds, but rather the sort that comes with the joy of remembering and admiring someone who, with delicacy and aplomb, showed audiences that the poetry of daily life was also the stuff of great cinema. With Varda, you watch one of her films and want to invite her for a coffee. Once I tried to interview her, in Spanish and over the phone (the nerve I had!), but it didn’t work out. I usually feel the need to talk with those masterful creators first-hand.

Not everyone who dedicates themselves to cinema has the power to become what in Spanish we call maestros—both masters and teachers of their craft. There are many great films, but very few maestros. Like many others, I became a lover of the silver screen with Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola. I was left speechless by Taxi Driver (1976) and The Godfather (1972), and I return to them when I need them. But I could only admire them. They didn’t light the same creative fire that Varda did. I’m convinced that the issue of money came between us.

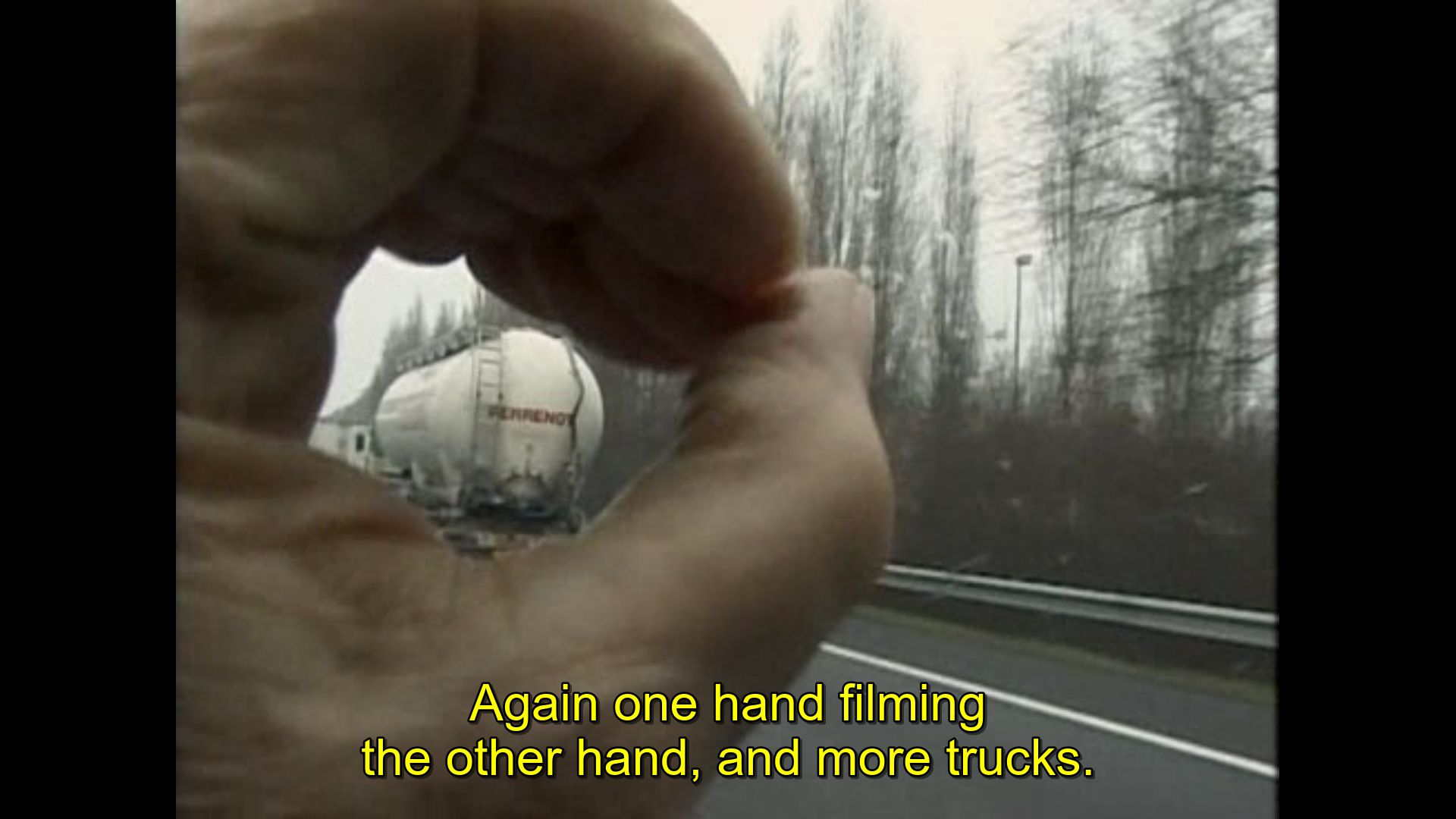

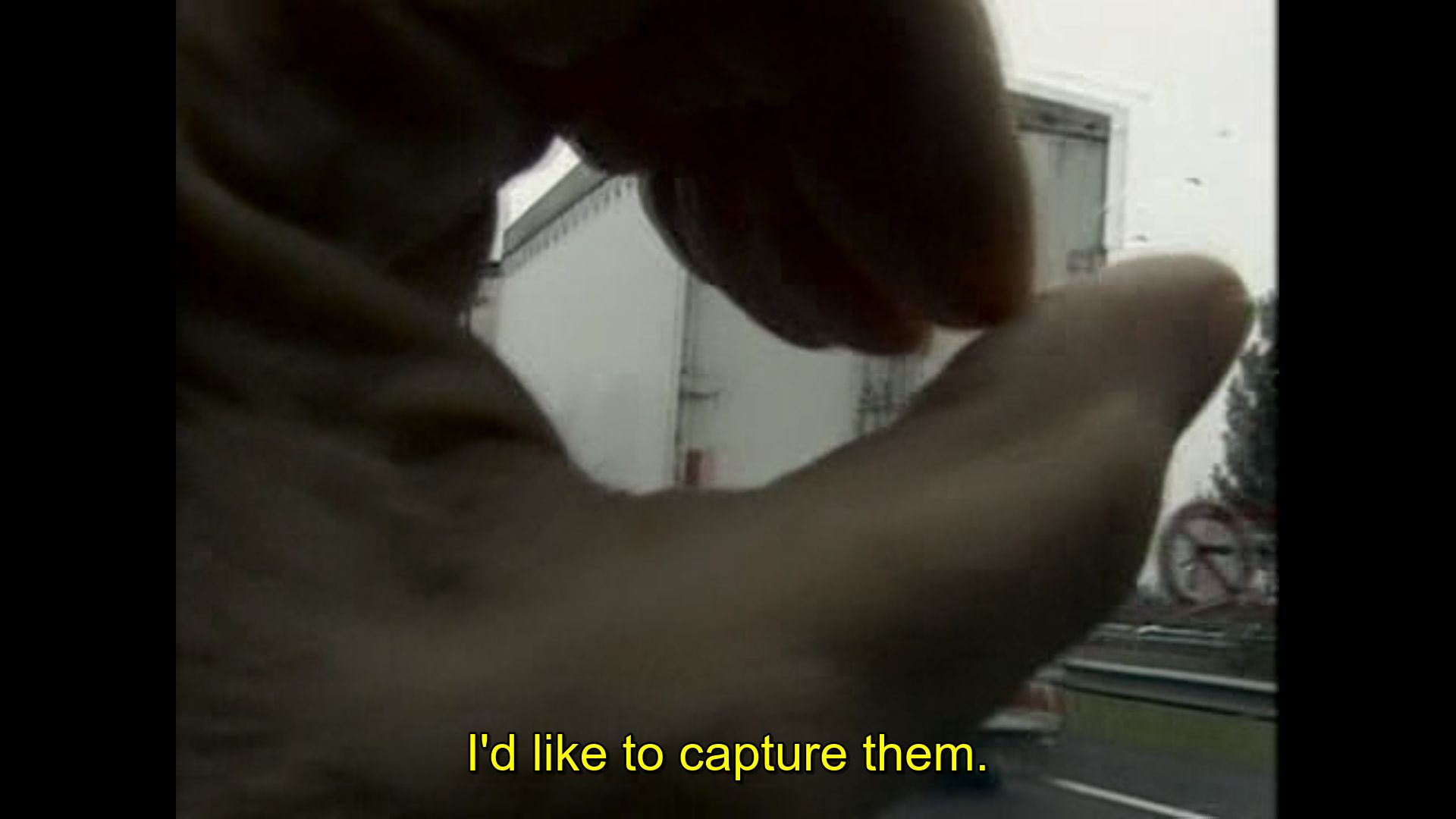

In The Gleaners and I, there’s a scene where Varda films her hands with a small digital camera. And she plays at catching the lorries driving along a French road with her hands. And she plays with the lens cover of the camera. And she shows her hands wrinkled by the passage of time. It was the first time I’d seen anything like it in cinema. This small gesture – slight, playful, maybe even spontaneous – pulled me away from the seriousness of the big cameras and the big studios of other filmmakers, the ones I could only admire.

Stills from The Gleaners and I (2000)

Agnès Varda is a maestra because every one of her cinematic projects – be it a documentary, a short, a full-length feature – invites you to create something. I like to think of her films as enduring projects that are difficult to label, that are constantly mutating, evolving.

Cinema and literature are two art forms full of rules. The fear of not paying due respect to the classics, snobbishness about the specific cultural heritage that you have to consider before you can even start making anything, and of course, the people who hold you back. Varda gives ultimate priority to intuition and play. This might be the key to her unique cinema.

In 1995, when cinema celebrated its 100th birthday, Varda made A Hundred and One Nights, a fable about Simon Cinéma (played by Michel Piccoli). Simon Cinéma is cinema, and also a person of flesh and blood. He’s Marcello Mastroianni’s friend. He lives in a mansion. Both Robert de Niro and Catherine Deneuve come to visit. It’s utter madness. Varda herself declared the film a failure, but at her level it hardly matters. Whenever we want to understand the spirit of cinema’s centenary, this film offers a way in.

I have always thought that the most talented filmmakers in history are those who could – and did – make films with lots of money, but who could also do so in more precarious contexts. Or essentially, when people talk about great directors who only make films in the USA, for me that’s all they are. Great, sure, but in the US, with that level of production, with those standards, with those rules. Steven Spielberg is a case in point. You cannot deny his status, but he only makes that kind of cinema. What would a Spielberg feature look like, filmed on a shoestring budget, in Chile, Uruguay or Peru?

A much more worthwhile example would be Luis Buñuel, a director that Varda admired greatly. The Spanish-Mexican filmmaker made both big and small films in countries like Spain, Mexico, and France, and even a few co-productions between Mexico and the US, in English with international actors. It could be said that Spielberg is uninterested in making cinema out of his comfort zone. And I could respond that it’s true, that not everyone is ready to break the rules and take risks. Buñuel took risks. Agnès Varda did too.

There is so much still to learn about the maestra Agnès Varda. As often happens, since her passing, her films are now easier to find and come with better subtitles. It’s not the point of this crónica, but it was beyond difficult to get an Agnès Varda DVD in the 2000s in Chile. All South American cinephiles have a love-hate relationship with Brazilian DVDs and their Portuñol subtitles, that blend of Spanish and Portuguese. That said, the effort made the rewards much greater. It was watching a documentary that changed you, that motivated you to create everything that you’d always been told couldn’t be done. Everything else paled in comparison, even those dubious subtitles.

In 2017, Varda directed and starred in the documentary Faces Places with the photographer JR. They tour through rural France, meeting everyday people and taking their portraits to blow up and paste on buildings. There’s a fundamental curiosity in this film, in the stories of those anonymous people, in exploring social relationships in the age of the smartphone. The documentary should be screened in every school in Chile and across the world. It is often said that cinema is not life, but that it tries to be. When it comes to Faces Places, I dare say that in that film, life resists the passing of time. The photos plastered on the walls may disappear, but the film that captures these photos is the closest thing to immortality. That’s no small thing. And a film-lover’s fact: you can hardly fail to mention that Varda received the honorary Oscar for her career that year, as well as a nomination for best documentary for Faces Places. Another moment of madness.

Why Agnès Varda? They asked, and I answered. Even if I fell short. I would need a whole book to do her justice. She was the only woman of the French New Wave. Her links to feminism date back to the 60s, and her great classic of that period, Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962), deserves a special look and its own essay. In fact, Faces Places cites that film directly, with a huge still from the film pasted in an ephemeral place. It seems as if all of Varda’s films are a rejection of everything done out of obligation to the industry rulebook. Varda’s thing is not just breaking the rules, but playing with them. At the Locarno International Film Festival in 2014, she declared: ‘At the time of the so-called new wave, there were other women making films. If they did not last, it was not because they were women, but because they weren’t as ambitious or stubborn as me when it came to experimenting.’

I don’t know if inspiration exists nor do I know what that word truly means. The only thing I can say is that Agnès Varda’s films make me smile, make me want to write, and give me a genuine desire to interact with the world around me.